From Ceasefire to Peace Deal: Setting Down Arms in Sudan?

Has Sudan’s brutal conflict reached the final ripening point, where externally-led mediation can be a success?

Malka, a displaced mother, carries her 1-year-old daughter Sahar, who is suffering severe acute malnutrition outside of her house in El Houry Gathering Point for internally displaced persons in Gedaref state. November 2024 (UNICEF/UNI689368/Ahmed Mohamed El Fatih)

The Rapid Support Forces (RSF), a paramilitary group active in Sudan, has agreed to a US and Arab nations-led humanitarian ceasefire for a period of 3 months [1], coming as a beacon of hope which may indicate future peace talks with the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF).

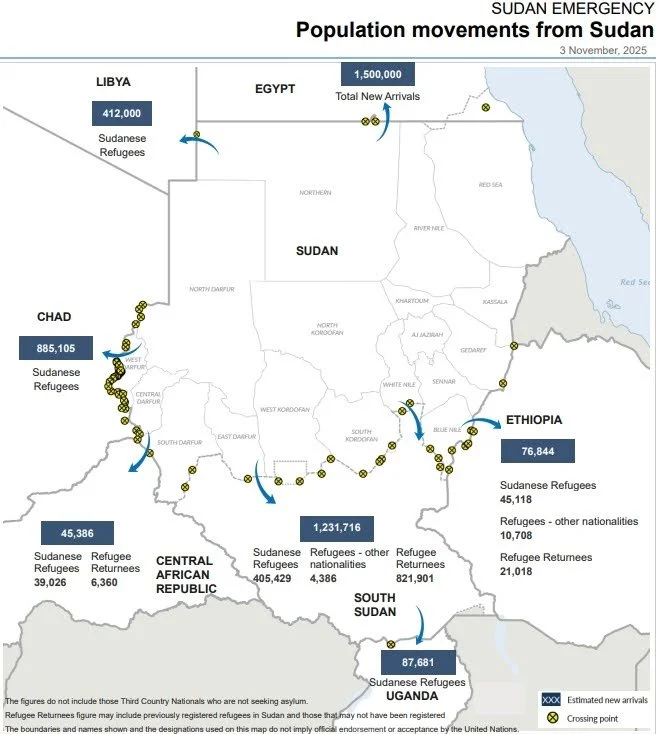

Sudan has been in a devastating war since 15th April, 2023, with at least 20,000 casualties, with thousands more facing a humanitarian crisis. Exact reporting is unclear, given the Sudanese government’s hostility towards humanitarian presence, and thus data-gathering activities, according to Nathaniel Raymound, Executive Director of the Humanitarian Research Lab [2]. The RSF was originally developed in 2013 by the official government to combat Sudanese rebel groups, and grew in recognition and numbers to eventually oppose the control of the SAF. The paramilitary group has seized significant regional assets in el-Fasher, Darfur, Khartoum, Kordofan, and Gezira, controlling Sudan’s border with Libya and Egypt [3], challenging the SAF’s capacity to maintain strong ties to the affected regions. The SAF has historically comprised pro-Sudanese national parties, and is overseen by Sudan’s Ministry of Defense.

Map Source Data: UNHCR and Government for Operational Data Portal. Published on 3rd November 2025

Continued artillery fire, drone strikes, and territorial advancement have forcibly displaced (internally and externally) more than 12 million individuals to date in what was named the “world’s largest humanitarian crisis” in April 2025 by the United Nations (UN). Another 30.4 million people face a growing emergency of malnutrition, dehydration, and access to an acceptable standard of living or shelter from violence. Roughly 50% of displaced persons are children, which, according to the International Rescue Committee and UN High Commission for Refugees, names Sudan as the world's largest child displacement crisis. Ongoing violence has also forced key educational centres to close due to destruction, leaving 19 million school-aged children without access to formal education [4]. This is highly detrimental to current and future population development, as youth struggle with essential skills including reading, writing, and opportunities to learn socialisation and community building: values which are integral to rebuilding social cohesion in Sudan.

Sudan’s humanitarian crisis also disproportionately affects women and girls, as evidenced by a report published by UN Women on the status of gender-based implications of violence [5]. Since 2023, sexual and gender-based violence has tripled, while a closure of 80% of the country’s hospital services has stagnated birth rates and increased malnutrition significantly. Women continue to be excluded from peace processes, including discussions in the Jeddah Process, Saudi Arabia, and the current ceasefire proposal.

Leading the ceasefire proposal is a Joint Operational Committee on diplomatic relations with Saudi Arabia, Egypt, the United Arab Emirates (UAE)– colloquially referred to as the ‘Quad’, and the United States. Tabled on 25th October in Washington, the initiative targets collective security priorities: humanitarian access, a lasting ceasefire, and an end to third-party military support. It follows extensive talks beginning on 12th September, where a pivotal blueprint was proposed for ending Sudan’s catastrophic violence [6]. Original terms within those talks led to a joint statement, with the following conditions: sovereignty for Sudan, unobstructed access to humanitarian aid, and an end to external military support and removal of troops. It also outlined that an “inclusive and transparent transition process” should be implemented over a nine-month period to reach a stable and independent governance structure for Sudan, and an initial 3-month humanitarian ceasefire– and eventually, leading to a more permanent truce.

The initial agreement reached on 6th November, 2025, is significant given the alarming increase in reporting of mass atrocities including the use of rape as a weapon of war, massacres, and looting carried out by both the RSF and SAF. International outrage for Sudan’s crisis has grown substantively over the 30-month-long civil war, including UN reporting, case-building for war crimes at the International Criminal Court, and social media activism aiming to alleviate misinformation to Sudanese citizens. However, are recognition of atrocities and an agreement to a ceasefire proposal reliable indicators of future stability in Sudan’s normalised culture of violence?

Contributor to The Conversation, Samir Ramzy, suggests that previous efforts to bring a permanent ceasefire and further institutional support to Sudan have failed for three reasons: significant proposal differences between mediators and the RSF, the inability of the SAF and RSF to identify a mutually hurting stalemate, and tensions between the US and Quad actors. While all three reasons hold true– parties at war must reach a mutual ‘ripening point’ at which they will willingly enter into negotiations– a fourth point may be added: the involvement of biased parties in mediation strategies continues to impede the potential for a reformed government in Sudan [7].

To address Ramzy’s first point, both paramilitary and legitimate government forces must be included in post-arms reforms of Sudan in order to create a political system in which root causes of the war are addressed. Regarding the ‘ripening moment’: UN Secretary-General António Guterres has declared the civil war to be “spiraling out of control” during the World Summit for Social Development in Doha [8]. At what cost can both parties continue? And lastly, persistent tensions between the US and Quad members, particularly on the question of Islamic influence, arms acquisition, and country-level support of the warring parties. Ramzy’s third point of internal divisions is a precursor to the proposed idea of diminished impartiality towards actors negatively affecting an effective and sustainable mediation strategy.

On one hand, Egypt has been accused of providing arms support and training to the SAF, often in opposition due to the UAE’s conflict-fueled gold economy, which serves as direct funding to the RSF. In 2024, the UAE imported 29 tonnes of gold from Sudan alone, raising eyebrows at the deep economic ties between Dubai’s companies linked to illicit gold laundering for RSF financers and the persistent conflict [9]. The Americans and Saudis have played roles in urging for a severance of arms to Sudanese forces, and a reformulation of sanctions on parties providing weaponry despite an existing arms embargo, which was renewed on September 12, 2025, under Resolution 2791 [10]. Under the second Trump Administration, Washington continues to be skeptical of the Islamic roots of RSF, yet it is a growing player in brokering peace deals where there are economic interests concerned: DRC, Ukraine, and now Sudan.

For Sudan’s ceasefire to evolve into a durable peace agreement, external mediators must commit not only to neutrality but to addressing the war’s economic drivers, history of embedded violence, and gendered impacts. Without substantive impartial governance reform and accountability, this proposal risks becoming yet another temporary pause in Sudan’s cycle of conflict.

Sources

[1] Khaled, Fatma. “Rapid Support Forces Agree to Humanitarian Truce with Sudanese Military.” AP News, 6 Nov. 2025, apnews.com/article/sudan-talks-paramilitaries-agrees-truce-c95d461ffb963f6a0214cb717b11c488.

[2] Roberts, Leslie. “How Many Have Died in Sudan’s Civil War? Satellite Images and Models Offer Clues.” Science.org, 2025, www.science.org/content/article/how-many-have-died-sudan-s-civil-war-satellite-images-and-models-offer-clues, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.zvussc0.

[3] Ali, Rabia. “Territorial Control: Who Holds What in Sudan’s War?” Aa.com.tr, 2025, www.aa.com.tr/en/africa/territorial-control-who-holds-what-in-sudan-s-war/3734931.

[4] UNHCR. “Sudan Situation: UNHCR Appeal 2025.” UNHCR, 2025.

[5] UN Women. “The Impact of Sudan’s War on Women, Two Years on | UN Women – Headquarters.” UN Women – Headquarters, 9 Apr. 2025, www.unwomen.org/en/articles/explainer/the-impact-of-sudans-war-on-women-two-years-on.

[6] Boswell, Alan. “All Eyes on the Quad: How the U.S. And Its Partners Can Push for Peace in Sudan | International Crisis Group.” International Crisis Group, Oct. 2025, www.crisisgroup.org/africa/sudan-united-states-egypt-saudi-arabia-united-arab-emirates/all-eyes-quad-how-us-and-its-partners-can-push-peace-sudan.

[7] Ramzy, Samir. “Peace in Sudan? 3 Reasons Why Mediation Hasn’t Worked so Far.” The Conversation, 31 Oct. 2025, theconversation.com/peace-in-sudan-3-reasons-why-mediation-hasnt-worked-so-far-268541, https://doi.org/10.64628/aaj.t34kv3hhk. Accessed 13 Nov. 2025.

[8] Wintour, Patrick. “Sudan Civil War Spiralling out of Control, UN Secretary General Says.” The Guardian, 4 Nov. 2025, www.theguardian.com/world/2025/nov/04/sudan-civil-war-spiralling-out-of-control-un-secretary-general-says.

[9] Soguel, Dominique, and Pauline Turuban graphics. “As Sudan’s Agony Deepens, Scrutiny Sharpens on UAE and Gold.” Swissinfo.ch, 5 Nov. 2025, www.swissinfo.ch/eng/international-geneva/sudan-war-uae-gold-trade-geneva/90284839. Accessed 13 Nov. 2025.

[10] Meetings Coverage- UN Security Council. “Security Council Renews Sudan Sanctions Regime, Unanimously Adopting Resolution 2791 (2025) | Meetings Coverage and Press Releases.” Un.org, 12 Sept. 2025, press.un.org/en/2025/sc16165.doc.htm.

Maps and Pictures:

UNHCR . “Sudan Situation Map Weekly Regional Update - 03 Nov 2025.” UNHCR Operational Data Portal (ODP), 2025, data.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/119534.

See source (4), UN Women.