Haiti’s War for Self-Determination — The Gang Violence in Context

“If we must die, we will die standing…” a protester demonstrating in Port-au-Prince for the end of the gang violence and accountability for the temporary government told Le Nouvelliste in March 2025 [1].

A woman sweeps debris next to a blazing barricade set up by demonstrators during a protest against insecurity in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, Wednesday, April 2, 2025. (AP Photo/Odelyn Joseph)

Haiti has been engulfed in a dire security and humanitarian crisis since 2021. The conflict arose out of increased economic inequality and failing governance after the assassination of President Jovenel Moïse [2]. Moïse’s presidency was marred by accusations of corruption, authoritarianism, and ineffective governance. His assassination left a power vacuum that exacerbated the nation’s instability, allowing the country’s already fragile institutions to crumble further and creating the opportunity for gangs to expand their control [3].

As of April, the over 200 recognized armed gangs in Haiti control approximately 85% of the capital, Port-au-Prince. The gangs are expanding their reach into the nearby district of Pacot, the commune of Kenscoff, and towards the Centre and Artibonite Departments [4]. In 2024 alone, at least 5,600 people were killed in gang-related violence [5]. According to the UN Office of the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA), 5.5 million Haitians remain outside the reach of humanitarian responses [6]. More than 1 million people are now displaced— internally, in the Dominican Republic, or seeking asylum outside of the island.

Haiti’s gangs operate with deliberate strategy, even if through seemingly random violence. Their main goals include territorial control, economic gain, political leverage, protection of their community, survival, autonomy, and disruption of state interventions. They primarily target market vendors, transport workers, small business owners, women and girls, teachers, rival gang members, government officials, and human rights defenders. Civilians face the brunt of this violence, through extortion, sexual and gender-based violence, and forced displacement.

The gangs deploy a range of aggressive tactics through the use of automatic weapons; blockades of critical infrastructure, such as fuel depots and ports, to pressure the state or undermine rivals; and the dissemination of propaganda through performative public violence, graffiti, and social media. They have forced an environment of fear and impunity, exerting coercive control through targeted assassinations, indiscriminate killings, and street tribunals [7].

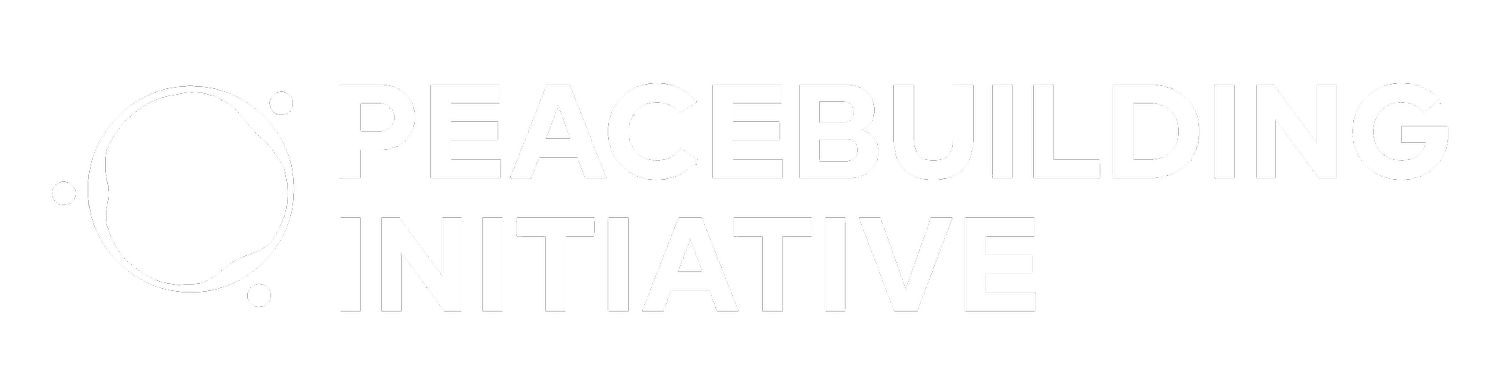

Haiti: Gangs and Vigilantes Thrive Amid Political Deadlock Conflict Map by ACLED, January 17, 2024. https://acleddata.com/conflict-watchlist-2024/haiti/.

Despite the scale of the violence, Haiti’s crisis struggles to attract sustained international attention. Support for addressing the humanitarian crisis and political instability remains deeply insufficient [8]. The most significant response has been the UN’s multinational security mission, deployed to assist the Haitian interim government, Temporary Presidential Council (TPC), in curbing the violence. Yet the mission suffers from severe underfunding and faces widespread local resistance, as many Haitians distrust the interim government due to its perceived corruption [9].

The crisis in Haiti did not develop overnight, and the global community’s neglect is not a mere symptom of indifference. Haiti’s conflict is deeply rooted in the legacies of colonialism and imperialism. International neglect reflects a deliberate avoidance of accountability for its role in shaping Haiti’s political, economic, and social instability and an effort to profit from the chaos it helped create.

Haitian revolution 1791. (Photo by: Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

The Historical Roots of Haiti’s Crisis

Haiti’s colonial and imperial history laid the groundwork for President Moïse’s authoritarian rule, the country’s enduring economic struggles, and its ongoing conflict.

Under French colonial rule, Haiti was the richest colony in the 18th century, due to its production of sugar and coffee and France’s reliance on the transatlantic slave trade [10]. By 1780, approximately 500,000 enslaved Africans in Haiti were responsible for France’s extreme wealth [11]]. In 1804, Haiti became the first nation in the Americas to overthrow colonial rule and the first free Black republic. However, after winning independence, Haiti was forced to pay reparations to France for its “property” loss, including land and enslaved people – a debt which stunted the nation’s development for generations [12].

Haiti was further destabilized by the United States’ 1915 Occupation of the country. The US invaded and occupied Haiti from 1915 to 1934 to “stabilize” the country and mold it into an extractive economy and friendly democracy. During this time, the US installed “favorable” leaders, brutally oppressed the Haitian resistance by deepening income and social inequality, and institutionalized economic dependency on the US [13].

Just three years after the US occupation ended, one of the most violent episodes in Haitian history occurred. In 1937, Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo ordered the massacre of thousands of Haitians and Dominicans of Haitian descent living near the border in what became known as the Parsley Massacre. This act of ethnic violence was justified through anti-Black, xenophobic rhetoric and a broader project of Dominican nationalism rooted in whiteness and the rejection of Haitian identity [14]. Trujillo stayed in power until 1961, facing few lasting consequences after his genocidal project.

More recently, the neoliberal policies promoted by international institutions in the 1980s and 1990s further eroded Haiti’s sovereignty. In exchange for humanitarian aid to address a food crisis, Haiti was required to adopt neoliberal economic reforms. However, the country entered the global market at a significant disadvantage, competing with more industrialized economies while lacking the infrastructure and production capacity to sustain itself. Structural adjustment programs from the IMF and World Bank forced Haiti to reduce public spending, privatize key state functions, and open its markets to foreign goods. These changes devastated domestic industries, particularly agriculture, which were highly vulnerable to external shocks after neoliberal restructuring. As subsidized imports flooded the market, local producers were driven out of business, deepening economic dependency and accelerating cycles of poverty [15].

Health Care Delivery, Haitian Health Foundation

Resistance and the Fight for Self-Determination

Despite centuries of foreign involvement and economic exploitation, Haitians choose to resist. While gang violence has brought immense suffering, the roots of the violence lie in a history of systemic abandonment, foreign intervention, and economic disenfranchisement. It reflects not just lawlessness, but a violent struggle over power and autonomy for a country and people long denied both due to their defiance and Blackness.The current conflict is not just a battle for domestic control; it is a generational battle for independence started in the 18th century.

Haitians are resisting not only through violence. Local women’s groups, youth organizers, mutual aid networks, and diaspora communities are leading efforts to rebuild Haitian society from the ground up. Organizations like Fanm Deside have led gender-focused resistance efforts, offering trauma support, shelter, and leadership training for women in gang-controlled areas [16]. These forms of resistance represent not only survival strategies but also decolonial peacebuilding practices that challenge external interventions and center local visions for their communities. Rather than relying on international prescriptions, these movements embody sovereignty through solidarity, cultural preservation, and self-determination.

Edited by Chynna Bong A Jan and Tamiliniyaa Rangarajan

Consider donating to Haitian-run nonprofits fighting for peace and security in their communities:

Haitian Bridge Alliance: https://haitianbridgealliance.org/

Hands Up for Haiti: https://handsupforhaiti.org/about-us/

Haitian Health Foundation: https://www.haitianhealthfoundation.org/

Endnotes

[1] Sénat, J. D. (2025, March 19). Manifestations, attaques aux drones explosifs et offensive contre des quartiers ce mercredi. Le Nouvelliste. https://lenouvelliste.com/article/254362/manifestations-attaques-aux-drones-explosifs-et-offensive-contre-des-quartiers-ce-mercredi

[2] Council on Foreign Relations. (2024, June 27). Instability in Haiti. Global Conflict Tracker. https://www.cfr.org/global-conflict-tracker/conflict/instability-haiti

[3] Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect. (2025, March 14). Haiti. https://www.globalr2p.org/countries/haiti

[4] United Nations. (2025, May 11). Haiti: UN warns of worsening humanitarian crisis amid escalating gang violence. United Nations News. https://news.un.org/en/story/2025/05/1163076

[5] The Guardian. (2025, February 23). The Guardian view on Haiti’s deepening crisis: Abandoning people when they most need support. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2025/feb/23/the-guardian-view-on-haitis-deepening-crisis-abandoning-people-when-they-most-need-support

[6] United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. 2024. Haiti. UNOCHA. https://www.unocha.org/haiti

[7] International Crisis Group. (2025, February 19). Locked in transition: Politics and violence in Haiti (Latin America & Caribbean Report No. 107). International Crisis Group. https://www.crisisgroup.org/latin-america-caribbean/caribbean/haiti/107-locked-transition-politics-and-violence-haiti

[8] Coto, D., & Lederer, E. M. (2025, April 29). Haiti could face 'total chaos' without more international support, UN envoy warns. AP News. https://apnews.com/article/un-haiti-gangs-violence-chaos-kenya-funding-df2e837506653612d53cc7486f295c1a

[9] Bull, S. (2024, October 18). US-backed, Kenya-manned police mission in Haiti is struggling. Responsible Statecraft. https://responsiblestatecraft.org/gangs-police-haiti/

[10] Porter, C., Méheut, C., Gebrekidan, S., & McCann, A. (2022, May 20). Haiti's lost billions. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/05/20/world/americas/haiti-history-colonized-france.html

[11] Dubois, L. (2004). Avengers of the New World: The Story of the Haitian Revolution. Harvard University Press.

[12] Marcelin, F. (2010). La dette historique de Haïti et ses conséquences économiques. Presses Universitaires d'Haïti.

[13] Étienne, S. P. (2007). Chapitre 5. L’occupation américaine comme conséquence de l’effondrement de l’État haïtien (1915-1934). In L’histoire de l’occupation américaine en Haïti. Presses de l’Université de Montréal.

[14] Paulino, E., & García, S. (2013). Bearing Witness to Genocide: The 1937 Haitian Massacre and Border of Lights. Afro-Hispanic Review, 32(2), 111–118. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24585148

[15] Kelly, M. (2018). In dependence: Haiti in the period of neoliberalism. History in the Making, 11(1), Article 7. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/history-in-the-making/vol11/iss1/7

[16] Centre for International Studies and Cooperation (CECI). (2017, August 14). Fanm Deside: An organization that fights to improve the status of women in Haiti. https://ceci.org/en/news-and-events/fanm-deside-an-organization-that-fights-to-improve-the-status-of-women-in-haiti