Humanitarian Aid in Trump’s Second Term: The Early Months

US President Donald Trump signed Executive Order 14169 in January, 2025 ordering a 90 day pause on all US foreign assistance programs. In the developments that followed, US Secretary of State Marco Rubio named himself the interim head of USAid in March after announcing 83% of the agency’s aid projects were eliminated. Trump and Rubio in a cabinet meeting on 26 February, 2025. (Yahoo Images)

Since US President Donald Trump started his second term, his ‘Make America Great Again (MAGA)’ agenda has ushered in a wave of setbacks for liberal institutions and global cooperation.

Within hours of his inauguration, Trump signed executive orders withdrawing the US from the World Health Organisation (WHO) and the Paris Climate Accords, a confirmation of his disdain for multilateral governance frameworks [1]. Most recently, his agenda has involved revoking foreign student enrolment and research grants from renowned higher education institutions, such as Harvard, for being ‘anti-American’ [2].

This long list of reversals of government policies, also includes consequences for the flow of humanitarian aid.

American Aid Unravels: The January Stop Order and USAID

To begin understanding the contemporary humanitarian aid crisis, it is necessary to review the changes initiated by the Trump administration in January 2025.

Shortly after the three-phase ceasefire deal mandated a tense exchange of hostages between Israel and Hamas, US Secretary of State Marco Rubio issued an internal order to suspend foreign aid. With the exception of food aid and military assistance to Israel and Egypt, all assistance programs were to be halted until they were evaluated against Trump’s foreign policy [3]. This stop order applied to American contributions to international assistance channels through UN agencies, peacekeeping initiatives, and refugee programs.

As a result, the critical operations of the US Agency for International Aid and Development (USAID), which supports key nutrition, health, and vaccination programs across the world, have been affected. The Republican President accused the agency, which is responsible for American development and humanitarian aid worldwide, of being run by “radical left lunatics” and claimed that there was “tremendous fraud” going on [4].

Humanitarian Aid in Conflict Zones: Ukraine and Gaza

The developments in January immediately sparked conversation about how the global conflict landscape would be affected.

Although Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky confirmed that the order would not affect military aid to Ukraine, there were uncertainties surrounding the future of reconstruction aid for the country. Workers were instructed to halt projects involving education assistance, emergency maternal care, and childhood vaccinations. Similar concerns were discussed in the context of humanitarian assistance to Gaza, especially as Palestinians continue to grapple with harsh realities of the Israeli administration blocking aid. Even though the executive order was quickly followed up by a waiver, enabling emergency food assistance to Gaza and Sudan. However food is only one component of the broader humanitarian aid packages that conflict zones, in particular, urgently require.

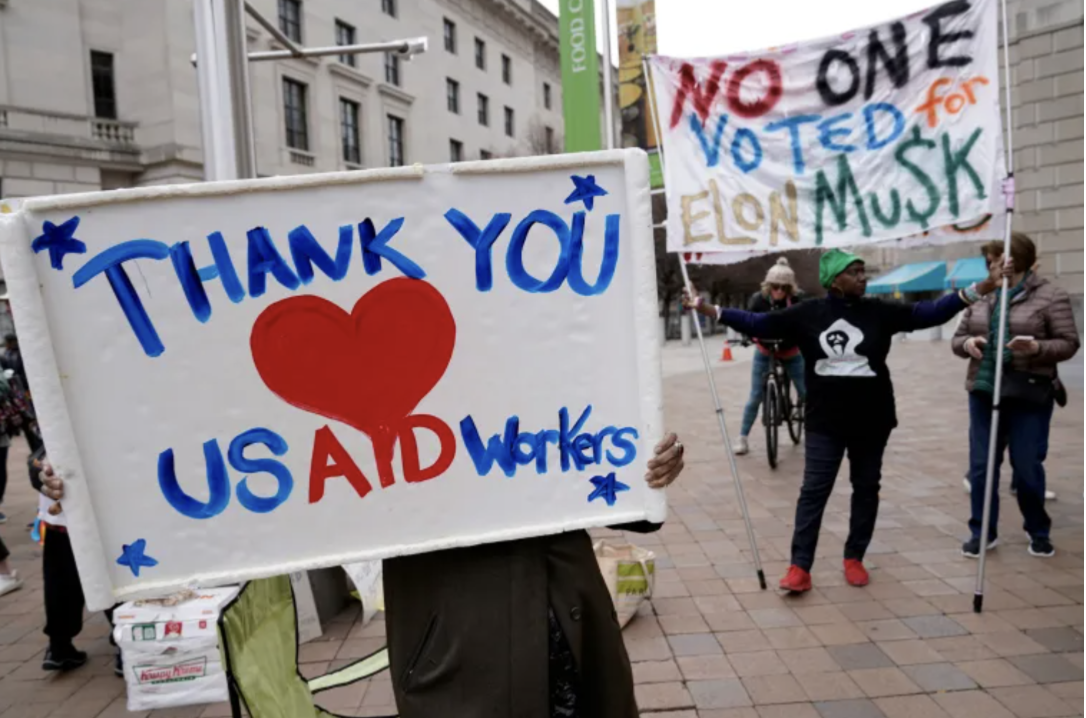

Protestors show support for USAID workers in Washington DC, on February 27, 2025. (AP News/ Jose Luis Magana)

A Snapshot of the Early Months: Healthcare and Democracy

In March, Rubio announced that roughly 5,200 of USAID’s 6,200 programs had been terminated, with the surviving ones slated to be absorbed by the state department [5]. Documents released subsequently, however, revealed that the administration had terminated 86% of the programs as opposed to the 83% reported by the US Secretary.

This is in spite of internal memos circulated by senior USAID leaders which estimated that one million children will go untreated for malnutrition, up to 166,000 people will die from malaria, and 200,000 children will be paralysed by malaria over the next decade, if these programs were shut down [6]. The breakdown of healthcare systems, especially in conflict zones where resources are already scarce, will lead to destabilising trajectories.

In addition to food and healthcare, democracy programs have also been affected by the cuts in humanitarian assistance. Financial support from USAid and the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) is crucial in running human rights and civic engagement NGOs in the MENA region. These, in turn, fund social movements and provide grants for the relocation and protections of activists. This deepens the already existing tensions caused by American regional democracy funding shifting to projects less antagonistic to MENA governments since the aftermath of the Arab Spring [7].

Alternative Donors in an America First Era

The international humanitarian sector’s reliance on Washington for nearly 40% of its funding, has inflicted an unprecedented funding crisis right as conflicts worsen in Sudan, Yemen, and Haiti [8]. Trump recently agreed that while the effects of his cuts were “devastating,” he hoped that this would push other countries to chip in instead [9]. In a clear iteration of his ‘America First’ doctrine, his comments came in the midst of South African President Cyril Ramaphosa’s visit to the White House.

The US cuts have evaporated nearly $436 million in annual funding for HIV treatment and prevention in South Africa, which runs the largest HIV treatment network in the world [7]. The crisis caused by the American President’s withdrawal of aid, however, has only been compounded by the fact that countries such as the UK, Germany, France, and Switzerland had already announced reductions to international cooperation and aid budgets. Although the possibility of private donors stepping in has been discussed, it is unlikely that they can match the US’s former contributions.

Moreover, the blurring of public and commercial interests in the American landscape – evident in the Elon Musk-led Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) or the Trump Organization’s entanglement in the President’s Middle East visit [8, 9] – will certainly complicate private channels of aid. Meanwhile, the speculation that China or the Gulf countries might step in as alternative donors remains unlikely, at best. Any such transition would require both time and institutional restructuring, and would be unlikely to keep pace with the rapid scale of the U.S. withdrawal [10].

South African President Cyril Ramaphosa with US President Donald Trump during his visit to the White House on 21 May, 2025. (Reuters)

Future American Trajectories: Peacebuilding and Accountability

The aid cuts have added to domestic concerns about government accountability. With the criteria used to determine which USAid programs get cut remaining opaque, it will become increasingly difficult to challenge and overturn the administration’s decisions.

The halting of emergency assistance and democracy programs signals repercussions for America’s commitment to peacebuilding initiatives in the long run. While Trump’s administration continues to headline conflict resolution efforts, it is important to keep in mind that they are often bilateral engagements and embroiled with conditionalities, primarily serving American interests. Although outside the purview of humanitarian aid, the recently signed minerals deal between the US and Ukraine created an incentive for the former to continue providing military assistance to the latter [14].

The MAGA doctrine’s reluctance to support global aid channels may stem from the fact that countries in need of humanitarian assistance do not offer immediate economic returns. The early months of Trump’s second presidential term have decisively reversed the US diplomatic strategy of providing humanitarian aid to gain global influence. The origins of this strategy, though highly circumstantial and instrumental, date back to 1919 when the American Relief Administration (ARA) was established to distribute food aid after World War I [15].

The consequences of reversing such a concretely embedded strategy are already beginning to unravel. In order to counter the impact on the international political landscape, it is necessary to look into global aid restructuring efforts – which are both costly and time consuming – as the US shows no indication of reversing its new policies.

Edited by Chynna Bong A Jan and Pilar Alejandra Paradiso

Endnotes

[1] Guardian Staff (2025, April 30). All the executive orders Trump has signed so far. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2025/jan/29/donald-trump-executive-orders-signed-list

[2] Raymond, N., & Hesson, T. (2025, May 23). Trump administration blocks Harvard from enrolling foreign students, threatens broader crackdown. Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/world/us/trump-blocks-harvards-ability-enroll-international-students-nyt-reports-2025-05-22/

[3] Pamuk, H., & Psaledakis, D. (2025, January 24). US issues broad freeze on foreign aid after Trump orders review. Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/world/us/trump-pause-applies-all-foreign-aid-israel-egypt-get-waiver-says-state-dept-memo-2025-01-24/

[4] Hutzler, A., Pereira, I., Chang, E., Pineda-Salgado, A., Deliso, M., & Reinstein, J. (2025, February 3). Trump 2nd term updates: Trump says USAID is run by “radical lunatics.” ABC News. Retrieved from https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/live-updates/trump-2nd-term-live-updates-executive-action-plans?id=117934786&entryId=118378868

[5] Gedeon, J. (2025, March 11). Rubio says 83% of USAid programs terminated after six-week purge. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2025/mar/10/marco-rubio-usaid-funding

[6] Barry-Jester, B. M. M. (2025, May 19). Trump officials thwarted warnings of death, illness in race to cut foreign aid. ProPublica. Retrieved from https://www.propublica.org/article/trump-doge-rubio-usaid-musk-death-toll-malaria-polio-tuberculosis

[7] Hearst, K. (2025, May 21). Middle East activists unable to relocate and survive after Trump’s USAID cuts. Middle East Eye. Retrieved from https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/usaid-implosion-leaves-mena-activists-mercy-political-crackdowns

[8] Burkhalter, D. (2025, May 14). Trump’s aid cuts plunge humanitarian sector into existential crisis. SWI swissinfo.ch. Retrieved from https://www.swissinfo.ch/eng/international-geneva/trumps-aid-cuts-plunge-humanitarian-sector-into-existential-crisis/89278455

[9] Reuters. (2025, May 21). Trump calls his own foreign aid cuts at USAID “devastating.” Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/world/us/trump-calls-his-own-foreign-aid-cuts-usaid-devastating-2025-05-21/

[10] Michelle Gumede Associated Press & ABC News. (2025, May 21). South Africa says its budget can’t cover for the deep US cuts in foreign aid. ABC News. Retrieved from https://abcnews.go.com/International/wireStory/south-africa-budget-cover-deep-us-cuts-foreign-122038943

[11] Kilgore, E. (2025, May 25). Musk’s legacy is making Trump’s outrageous agenda seem tame. Intelligencer. Retrieved from https://nymag.com/intelligencer/article/elon-musk-legacy.html

[12] Weissert, W. (2025, May 14). Trump’s Middle East visit comes as his family business ties there grow. AP News. Retrieved from https://apnews.com/article/trump-business-interests-family-middle-east-cryptocurrency-cbb7d2354304ce0308800819944cf3f8

[13] Dikanska, C. (2025, April 15). Is Geneva prepared for Trump’s – and others’ – cuts to foreign aid? SWI swissinfo.ch. Retrieved from https://www.swissinfo.ch/eng/international-geneva/is-geneva-prepared-for-trumps-and-others-cuts-on-foreign-aid/89035253

[14] Geoghegan, P. K. J. F. a. T. (2025, May 1). Seven takeaways from Ukraine minerals deal. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c5yg456mzn8o

[15] Burkhalter, D. (2025, May 19). How the United States used humanitarian aid for influence. SWI swissinfo.ch. Retrieved from https://www.swissinfo.ch/eng/international-geneva/how-the-united-states-used-humanitarian-aid-for-influence/89342741